⭐️⭐️⭐️⭐️

The Eyes Are the Best Part by Monika Kim is one of those books that’s difficult to slot neatly into a single genre. It’s horror, yes, but not in the traditional sense. It’s also a family drama, a cultural study, and a descent into obsession and madness. The story follows Ji-won, a Korean-American woman whose family life is slowly crumbling around her. Her father leaves, her mother is left reeling, her sister is struggling to cope, and into this fragile situation walks George, her mother’s new white boyfriend, who exudes the sort of smug ignorance and quiet fetishisation that instantly makes your skin crawl. Kim doesn’t waste time making him likeable – he’s written to get under your skin – but what’s most interesting is how Ji-won’s disgust towards him begins to twist into something darker.

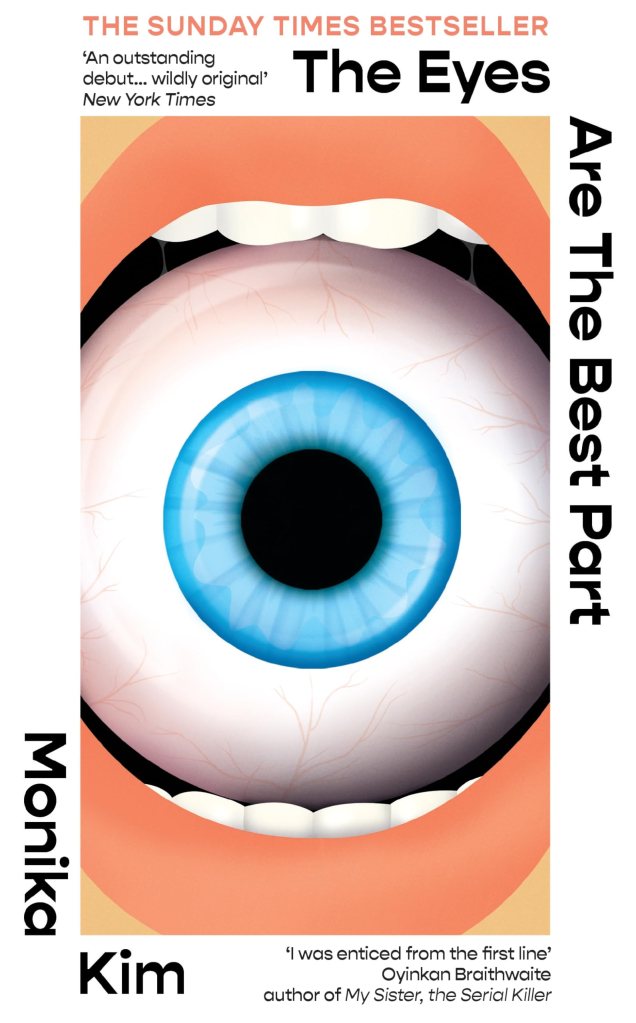

At the heart of the novel is this motif of eyes. Early on, there’s a family dinner where Ji-won’s mother eats fish eyes, a Korean tradition meant to bring luck. It’s one of those scenes that seems harmless at first, almost tender, but it plants a seed. Soon Ji-won starts fixating on eyes, particularly blue eyes, and the story begins to slip into something strange and grotesque. She dreams of eyes, craves them, and begins to imagine violent acts connected to them. The title might sound poetic, but by the time you reach the second half of the book, it takes on a much more literal and stomach-turning meaning.

What makes this story stand out isn’t just its body horror but its emotional core. Kim captures that suffocating dynamic between mothers and daughters, especially within immigrant families, where love and duty often come entangled with guilt and silence. Ji-won’s mother is a woman broken by abandonment, and her dependence on men – first her husband, then George – feels both tragic and infuriating. Ji-won, on the other hand, carries the weight of being the eldest, of having to protect, explain, and translate for her family while suppressing her own unravelling. The way Kim writes their relationship feels raw and painfully believable. There’s no sentimentality here, just the weary honesty of people who love each other and still manage to hurt one another every day.

The horror itself is handled with subtlety for a while, more psychological than overt. Kim blurs the line between hallucination and reality so effectively that after a few chapters, you stop trying to separate the two. The surreal imagery – the shifting faces, the eyes that seem to follow Ji-won, the flashes of violence that may or may not be real – creates an atmosphere that’s constantly uneasy. You’re never sure what’s actually happening, which is exactly the point. It mirrors Ji-won’s fractured sense of self, her cultural displacement, and her inability to process grief or rage in a way that feels safe.

That said, the pacing can be a test of your patience. The first half of the novel is characterised by dream sequences, internal monologues, and family tension, with little movement. It’s beautifully written, but some readers might find themselves waiting for the story to truly begin. When the horror does finally surface in full, it’s both shocking and slightly rushed, as though all that slow-burning tension suddenly bursts in one violent exhale. The ending in particular asks a lot from the reader – it leans heavily on metaphor and ambiguity, and whether that works depends entirely on how you interpret the story’s reality. Some will find it haunting; others might feel it overreaches.

George and a few of the other male characters also risk being somewhat one-dimensional. They’re designed to represent the uglier sides of fetishisation and patriarchy, but sometimes that symbolism flattens them. Ji-won, though, feels fully alive – angry, confused, and often unlikable, but believable all the same. Her descent into obsession makes sense emotionally, even if the specifics of how far she goes occasionally stretch believability.

Still, despite those flaws, Kim’s debut is bold and memorable. It’s not polished in the conventional sense, but that rawness gives it power. The writing has a rhythmic, feverish quality that suits Ji-won’s mental state. The imagery lingers – fish eyes glinting on a plate, reflections that seem to blink back, dreams that taste of salt and blood. It’s the kind of book that stays under your skin for days, not because of jump scares but because of what it says about the quiet violence of identity, family, and being seen only through someone else’s gaze.

I’d call it a solid four out of five. It’s messy in places and occasionally too ambiguous for its own good, but it’s also fearless and deeply unsettling. Readers who enjoy psychological horror, cultural unease, and stories that blend realism with body horror will likely appreciate it. Those who prefer their horror straightforward might find it frustrating. Either way, The Eyes Are the Best Part is an impressive, uncomfortable debut that announces Monika Kim as a writer with something sharp and unflinching to say.